Iterative Prompting with LLM to limit Hallucination and tackle Ambiguity

Introduction

LLM’s Recent Boom

LLM’s have exploded in popularity in recent years due to its ability to generate human like response using data and deep neural networks trained with billions of parameters. With the introduction of a architecture called transformers, text generation is able to utilize attention mechisim to refer to prior part of the text state of art result in many text tasks(Vaswani et al., 2017). By jamming data into a model and using Human Reinforcement Learning, models such ChatGPT has taken natrual language processing to new heights (Ouyang et al., 2022).

Connection with Language Comprehension

Many existing works have been done not only to study the neurological and linguistics aspects of language. Studies have also shown evidence that the brain actively predicts upcoming words at multiple levels during natural language processing (Willems et al., 2016). This posts question whether the statistical nature of LLM has some similarity to human cognition but also sought to understand their black box like behavior. Although model have much larger access of information than human could in a life time, by age 10, an average person is exposed to 30-110 million words to gain linguistic competence (Hart & Risley, 1992; Hosseini et al., 2022). In comparison, GPT-3, has been exposed to over 200 billion words. That's around 2000 times more than a 10-year-old (Warstadt & Bowman, 2022). The work quantifies the contribution of distributional language information to mental state reasoning, and implies other innate or learned capacities are also necessary to fully explain human social cognition (Trott et al., 2023).

Problems of Large Language Model

The "good enough" (GE) representations concept proposed by Ferreira, Bailey, and Ferraro (2002) provides a useful framework for understanding the shallow reasoning abilities of large language models (LLMs). Just as humans create adequate but potentially flawed interpretations during language comprehension, LLMs are prone to superficial understandings and overlooking logical inconsistencies.

This manifests in the phenomenon of hallucination, where models confidently generate blatantly incorrect or illogical responses (Sinha et al., 2021). As demonstrated in the illustrative examples (Figure 1), LLMs like Claude and GPT-3.5 fail to detect obvious contradictions within simple prompts. When asked substantively identical questions with different superficial wording, the models produce mutually contradictory answers.

Similarly, LLMs also suffer from an aspect called hallucination (cite some random paper). This phenomenon occurs when a model confidently gives the non-factual or incorrect answer to a question. Take these two very short scenario we can prompt to ChatGPT for example:

Figure1:

- Prompt 1: "If there are 10 books in a room and I read 2, how many books are still in the room?"

- Prompt 2: "Sue drank her morning coffee before getting ready for work. She spilled the coffee on her white shirt. What color was the shirt?"

In my test, running on Claude2 and GPT-3.5 tubro(ChatGPT) resulted in direct answer 12. Yet the question itself is when an LLM generates two logically inconsistent sentences within the same context since self-contradictions guarantee exposing an LLM's lack of factuality.

Such responses indicate these models lack robust causal reasoning abilities and are swayed by surface-level cues. Their knowledge representations appear "good enough" for many purposes but crumble when probed by targeted contradictions.

Motivation

The parallels between human and LLM comprehension weaknesses underscore the need for interventions that push models past shallow pattern recognition. Just as human reasoning benefits from clarification prompts and breaking down problems, LLMs may likewise improve with proper scaffolding to encourage deeper logical thinking. However, more research is required to determine prompting approaches that efficiently instill stronger reasoning abilities.

One of experiment of mitigation have included coming up with pipeline to detect and correct contradiction that another model generates with some prompting(Mündler et el., 2023). This limits the completeness of the mitigation, since it can only act on the subsets of contradictions that were correctly identified. In addition, the methods relies on correcting the contradiction itself based on some ground truth provided. While still useful to see, this is could be impractical in conversational reasoning where limited context is provided to the model.

Putting it together

What if we ask the model to “critically reflect” on part of the question, as well as the response over and over again using logic to overcome this shallow understanding of question? Another possible approach to combat this hallucination is to have model to split up the question into subproblems and let itself iteratively. Given the sample prompt, Claude2 was not able to identity the ambiguity as shown in Figure 1, but was able to later find lapse in error by questioning its own interpretation of problem. This aligns with results have shown large language models have struggled recognizing errors ground truth while being highly accurate when given it and its task is simply to use logic to figure out (Mündler et el., 2023).

How does utilizing multi-step prompting strategies and hallucination checking affect the ability of large language models to eliminate self-contradictions during conversational reasoning without additional training data?

Method

Chain of thought prompting

The approach is very similar to how a human would solve any mathematical puzzles, multi-step chain of thought prompting (Wei et el., 2022) have solve this issue. For example, if given the task to figure out

- What is the number of letters in America raised to the 0.5 power?

The model could break this problem down two issue:

- Calculate the number of letters in the America

- Raise the previous response to 0.5 power

The hypothesis is that we can achieve a similar result but by tweaking the prompt to allow it to specifically check for any contradictions and ambiguity it finds in the question. For instance, as shown in Figure 1, if we explicitly tell the LLMs whether reading is the same as removing, it will realize the ambiguity in the question and be more holistic and accurate in its answer.

Stimuli: The stimuli will consist of 3000 open-ended, thought-provoking prompts designed to assess language model comprehension about ambiguity. Three sets of prompts will be constructed, each containing questions that require multi-step reasoning to answer fully.

Procedure:

- Baseline: Models will be given the prompts as-is, with no intervention or scaffolding. Their raw responses will be evaluated.

- Experimental: Three prompting strategies will be tested on the models:

- Subtask decomposition: The model will first be instructed to break down the prompt into sub-questions before attempting to answer the full prompt.

- Clarification: The model will be prompted to reword or clarify the original prompt before responding.

- Combined: The model will break down the prompt into sub-questions and clarify any ambiguities before providing the final response.

- The models will iteratively apply rewording, subdivision, and clarification as needed in responding to the prompts. Their responses after each strategy will be evaluated and compared to the no-intervention baseline.

- The three prompting strategies will be tested separately to determine the effect of each approach on comprehension.

Testing Results

The responses generated by the models under each prompting strategy will be evaluated and compared to the no-intervention baseline responses. Quantitative analysis will be performed by calculating BLEU scores to assess the similarity between the model responses and sample target answers. In addition, human evaluators will assess the correctness and coherence of the responses.

The key dependent variable is the model's ability to handle contradictions and reason through multi-step prompts, operationalized through both automated metrics (BLEU) and human judgements of response quality.

The independent variables are the prompting strategy (no intervention, subtask decomposition, clarification, combined). The model architecture and the dataset of prompts are control variables that will be kept consistent across conditions.

Analysis will determine whether the prompting interventions lead to significantly higher quality responses compared to baseline, providing insight into the effect of scaffolding on language model comprehension and reasoning. Differences between prompting strategies will also be analyzed to understand the relative contribution of subtask decomposition, clarification, and their combination on model performance.

Predicted Results

Predicted Results

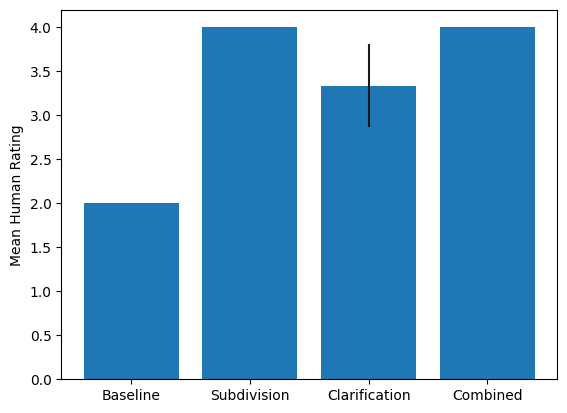

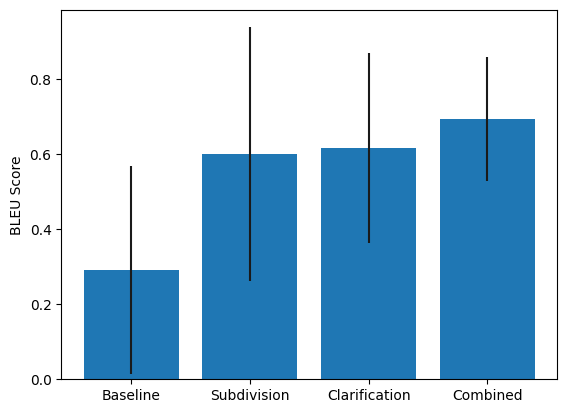

Based on prior work on prompting strategies for language models, we hypothesize:

- Models prompted with subtask decomposition will demonstrate improved performance on contradiction handling compared to no-prompt baseline, evidenced by higher BLEU scores and human rating scores.

- Clarification prompting will also improve scores relative to baseline, though possibly to a lesser degree than subtask decomposition.

- The combination approach utilizing both subdivision and clarification will show the greatest improvement over baseline.

We predict the prompting interventions will allow the models to respond more slowly and deliberately, focusing on step-wise coherence rather than jumping straight to a top-level response. This scaffolding emulates the iterative reasoning process a human would use to work through contradictory logic puzzles.

Visualization

Here is a rough projections of what the result would look like:

Mean Human rating (scale of 0 -5) for the four strategies:

Average BLUE Score (scale of 0 -1) for the four strategies compared to offical answer.

Discussion

Future of LLMs

If the results of the study is to align with my predictions, it could pave the way for future way to do prompt engineering and combat hallucination, one of the most crucial areas of large language model safety with its reasons remaining unknown to people still.

With the approach outlined in this proposed study, every single response of the conversation needs a chain of multiple prompts to generate close to error-free response. This approach would be extremely timely and cost-inefficient to implemented and use in real world applications.

If the results align with predictions that prompting strategies improve comprehension and reasoning, this study could open new avenues for prompt engineering to combat hallucination in large language models. Hallucination remains one of the most concerning and poorly understood risks of language models, thus developing techniques to enhance their logical consistency is crucial for safety.

Human Cognition

In terms of applying this concept for human cognition, As Trott, et el. notes, using LLMs as a theory's operationalization allows for more opportunities to test specific mechanisms and hypotheses (Trott et el, 2023). However, it is worth noting that these theories do not necessarily translate to human understanding and could possiblly be attributed for “statistics generally rather than a close mechanistic similarity” (Trott et el, 2023). Despite this limitation, I believe the result can prove useful insights in human understanding how humans tackle ambiguity and complexity within reasoning and help provide evidence grounds for future theories in the field.

Limitations

However, the prompting approach outlined here has significant limitations in real-world applications. Having a human in the loop to iteratively prompt clarification and subdivision of tasks is time-consuming and renders applications inefficient. Furthermore, it shifts the burden of reasoning wholly to the human operator, rather than developing the model's own capabilities.

This points to the need for further research into automating elements of the prompting interventions used here. Ideal would be the development of models capable of self-directed clarification, contradiction-checking, and subdivision of complex prompts. However, major advances in on-the-fly prompt engineering are still required to make robust reasoning scalable without intensive human oversight.

Improvements

Additionally, the prompts used in this study are limited in scope and may fail to expose contradictions in more open-ended contexts. Testing on broader domains and data is necessary to determine the general applicability of these interventions. Developing standardized benchmarks for contradictions and ambiguity could better track progress in this space.

In conclusion, this work offers a promising proof of concept but requires substantial follow-up to translate into solutions for unsafe reasoning in deployed language models. As models grow more powerful, improving their comprehension through tailored prompting strategies emerges as a critical area for continued research.

References (8 total)

- Trott, S., Jones, C., Chang, T., Michaelov, J., & Bergen, B. (2023). Do large language models know what humans know? Investigating belief attribution in machines. arXiv:2209.01515.

- Trott, S., & Bergen, B. (2022). Languages are efficient, but for whom? Cognition, 225, 105094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2022.105094

- Ferreira, F., & Patson, N. D. (2007). The ‘good enough’ approach to language comprehension. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1(1-2), 71-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00007.x

- Willems, R. M., Frank, S. L., Nijhof, A. D., Hagoort, P., & van den Bosch, A. (2016). Prediction during natural language comprehension. Cerebral Cortex, 26(6), 2506-2516.

- Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need.

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1992). American parenting of language-learning children: Persisting differences in family-child interactions observed in natural home environments. Developmental psychology, 28 (6), 1096.

- Warstadt, A., & Bowman, S. R. (2022). What artificial neural networks can tell us about human language acquisition. In Algebraic structures in natural language (pp. 17–60). CRC Press.

- Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright, C. L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K., Ray, A., Schulman, J., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L., Simens, M., Askell, A., Christiano, P., & Leike, J. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.02155.

- Mündler, N., He, J., Jenko, S., & Vechev, M. (2023). Self-contradictory hallucinations of large language models: Evaluation, detection and mitigation. arXiv:2305.15852

- Wei, J., Wang, J. X., Tay, Y., Bommasani, R., Raffel, C., Zhou, D., Chi, E. H., & Le, Q. V. (2022). Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.11903.

- Shridhar, K., Stolfo, A., & Sachan, M. (2022). Distilling reasoning capabilities into smaller language models. arXiv: 2212.00193